-

私人信念的拥护者认为,信念全然是私人之事,主观的理由是拥有信念的充分理由[1],信念是一种不需以诸如观察、断言以及推论为基础的自我知识,具有(1)第一人称身份(first-person identity);(2)第一人称视角(first-person perspective);(3)第一人称承诺(first-person commitment)以及(4)第一人称权威(first-person authority)等特征。(1)指第一人称最为清楚自己持有怎样的信念;(2)指第一人称最为清楚持有信念的理由;(3)指第一人称最为清楚自己对待信念的态度,例如信念度、真假态度;(4)则指第一人称的信念决定着相关的问题域,即能动者最为清楚自己的信念存在哪些问题,与哪些问题有关以及如何描述[2]。

本文旨在反对上述私人信念的观点,认为信念本质上是公共的。信念可以被外化为关于它的行动,拥有一个信念必须拥有文化共同体所拥有的信念整体。能动者(agent)作为共同体的一员,其信念必须能在公共交往的实践中被证成。第一人称视角和第三人称视角密不可分,我们只能以观察、判断和推论作为证成和理解信念的起点。戴维森和布兰顿的相关观点分别提供给我们理解和证成公共性的信念的解释及推论的思路。“信念本质上是公共的”这一观点还有助于解决关于信念的一些争议,本文最后以“摩尔悖论”为例,在运用这一观点解决实际问题的过程中,进一步加深对信念公共性的理解。

全文HTML

-

皮尔士认为信念和行动是密不可分的两个概念,在他看来,如果某个能动者S具有信念p,那么S必须具有以p为基础采取行动的倾向[3]。一旦实施倾向的条件被满足,信念便会转化为行动。皮尔士的推理可以归结为:

P1:S具有信念p,当且仅当,S具有基于p采取行动的倾向;

P2:S具有基于p采取行动的倾向,当且仅当,在特定的具体情况下S会以p为基础采取行动;

因此,S具有信念p,当且仅当,在特定的具体情况下S会以p为基础采取行动。[4]

皮尔士在逻辑上将信念与行动联系起来,认为信念可以外化为可观察的行动,信念不再全然是私人的事务,能动者若要合理地持有信念,必须保证他的行动可被理解或获得成功。人们也可由对行动的解释来理解行动者所持有的信念。

安斯康姆也将信念和行动联系起来,但不同于皮尔士单纯将两者在逻辑上联系起来的做法,安斯康姆把行动理解为一个“标志的意向行动”(token intentional action),该行动标志包含有一系列具有解释关系的行为,因此关于某一行动的信念不仅仅和行动本身有关,它还关涉到构成行动的一套动作。例如,向咖啡机中加咖啡豆和水,打开咖啡机开关,从冰箱中取出牛奶等行为构成了具有“做一杯牛奶咖啡”意向的行动,失去这些具体的行为要素,某个行动将会失去其“行动”的身份[5]。

根据劳伦斯的解释,安斯康姆实际上认为我们只能以“做一杯牛奶咖啡”这样的行动作为起点,这些行动所包含的行为在它们所共同构成的行动之下得到解释[6]。例如我们正是通过“做一杯牛奶咖啡”的行动来解释“取出牛奶”和“做黑咖啡”等行为,失去了关于“做一杯牛奶咖啡”的信念(意向)①,我们将无法理解基于这一信念所采取的行动中包含的行为。反向地表述该思想,我们认为如果一个行动是可被理解的,那么关于该行动的信念必定已经蕴含行动中所包含的行为间的解释关系。故而,信念不仅与外化的行动有关,信念本身已经隐含可被外化的、关于内容关系的解释。

① 我们在此将“信念”等同于“意向”,认为出于某些理由而行动(意向)和因为相信某些理由而行动(信念)在实践中是没有差别的。诸多哲学家,例如戴维森、哈曼、安斯康姆都曾讨论过两者间的关系,他们的观点大都试图把信念解释为某种意向,或把意向看作某种信念,或取消两者之间的差别。见SETIYA K. Intention[EB/OL].(2014-01-20)[2016-11].http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/intention/#IntBel。霍尔顿也通过研究发现,大部分时候,信念和意向在引导行动的效果上是一样的。见HOLTON R.Partial belief, partial intention[J]. Mind, 2008, 117(465):27-58。

然而,为什么信念本身已蕴含解释关系呢?当我们以“做一杯黑咖啡”这一信念作为基础而采取行动时,该行动不再是“做一杯牛奶咖啡”这一行动的一个步骤。要成功地完成“做一杯黑咖啡”的行动,我们必须能够区分出它和“做一杯牛奶咖啡”这一行动之间的区别,这就意味着在拥有一个信念时,我们同时必然具有许多其他信念,并且知道这些信念之间的联系。因为当我们相信“这是黑咖啡”时,我们必然相信黑咖啡不是牛奶咖啡,不是可乐,如此等等。我们只有在一个信念之网内才能获得与理解一个信念。这便导向了戴维森式的结论:我们不可能拥有一个独立的信念,拥有一个信念意味着拥有信念整体[7]。

信念整体中交织着各种解释关系,这些关系也相应于行动中涉及的事件间的关系脉络。只要能动者不是一个孤独的心灵而是某一共同体中的一员,能动者所具有的信念整体就必然能为其他共同体的成员所接受,他所具有的具体信念必然也能为其他成员所理解和持有。信念已经蕴含有可被接受的解释关系,这一事实说明能动者是以公共的标准,而非以私人的标准来生成其信念的。在此意义上,尽管信念为个人所拥有,但它本质上是公共的。

-

信念的公共性特征迫使我们重新探究对信念的证成。强调“信念是公共的”意味着信念的证成将会在公共的空间内完成,第三人称视角会被引入进来。例如,某甲声称自己“相信外面正在下雨”,在公共的维度内,他需要保证该信念和其他公共信念之间的融贯性,并试图让其他主体也接受他的信念。

“信念不全然是私人的事务”意味着能动者不可以合法地依据孤独的心灵或私人语言来“直接”证成信念。“信念的公共性”意味着能动者需要重视第三人称视角,将“他者”同样视为与自己相似的理性生物,证明自己的信念亦可为他者所理解和接受。这就意味着证成信念需要在主体间的交流、对话中进行。当研究信念的起点是对方可观察的行为,能动者对信念的表达构成一个基本的言语行为时,我们面临的是戴维森所谓的“彻底解释”的情形。

彻底解释是指在“翻译手册”不存在的情况下,我们只能根据彼此的可观察的理性行为来做出解释。戴维森的彻底解释理论从理性生物的信念、意向态度和信念的“真”出发,以外化的可观察的行为为解释依据;因为只有在把他者的某些言语表达看作是真的之情况下,我们才能结合具体的环境以及他者行为做出进一步的解释。戴维森认为解释者的“持真态度”(认为……是真的)是解释得以开始的条件,“持真态度”能够打破“除非我们知道某人所相信的东西,我们就不会知道他所意谓的东西;除非我们知道某人所意谓的东西,否则,我们就不会知道他所相信的东西”(即信念和意欲)这一循环[8]29。持真态度本身的依据则是戴维森所谓的“宽容原则”。宽容原则在此并不是作为一种选择而出现,它是作为一种必然而强加于我们的。倘若我们想要理解他人,我们则必须秉持宽容原则,必须假设我们与他人在很多问题上的看法是一致的[8]273。瓦希德进一步解释道:“宽容并不是对充分的解释的策略性的或形式上的限制,而是说话者的一种构成性条件。”[9]47-49依托于宽容原则,能动者的信念才是可被理解的,否则的话,信念便只是无意义的噪音。进一步地,只有在信念是有意义时,说话者才成为一个理性主体。宽容原则不仅构成理解的条件,也构成了成为理性生物的条件。遵守宽容原则的理性生物也是一个社会生物,他所持有的信念也应在社会性的交流中被理解和证成,因而有意义的信念本质上是公共的。

那么,如何证成公共信念呢?戴维森的观点建立在上一节中所揭示的信念的整体性特征之上。根据戴维森的说法,“一切信念都在下述这种涵义上被证成:它们为众多的其他信念所支持(否则的话,它们便不会是它们实际上所是的信念了),并且,它们具有据以推定其真实性的根据。……没有什么孤立的信念,不存在这样的信念,它没有据以对之做出推定的根据”[7]。一个信念的真之依据在于它所在的信念整体,因此,没有任何信念是孤立的。证成信念的整体论方式也同时说明了不存在私人的孤立的信念。

能动者的信念总是与其他的信念相融贯的,当他者要求能动者为其信念提供证成时,能动者将给出作为持有该信念理由的其他信念。如果在这种彻底解释的实践中,交流能够成功进行,能动者的信念便得以证成。然而,戴维森的表述似乎更多是结论性的,而未就交流实践的图景提供更多的细节。

-

戴维森把证成信念的起点设置在理性生物的意向状态和可观察的行为之上,这就意味着只要具有理性(rationality)的生物均可参与到交流之中,而不要求理性生物必须是居住在概念空间中的成熟居民。也就是说,任何能够说出包含命题态度的表达式(而非判断)的生物都有资格是能动者。不同于戴维森,布兰顿把“判断”视为我们可以对之负责的最小单位[10]160。有意义的信念至少是一个判断。判断是具有智识能力(sapience)的人类独有的,但具有感性能力(sentience)的生物也可能具有命题态度①,因而戴维森哲学能够容纳人与动物之间的连续性,布兰顿哲学则开始于人与动物之间的断裂之处[10]1-2。在此意义上,两人的思想可以互补。

① 一般认为,拥有一个命题态度就是拥有某一信念、期待、倾向等,并且该命题态度可为语句所表达,尽管它可能并不是以语句的形式出现。按照这种理解,运用感性能力能够获取命题态度,拥有感性能力的动物也因此能够具有命题态度。由于命题态度可被语句所表达而成为判断的单位,所以从感性能力和命题态度出发隐在地承诺了人与动物之间的连续性。相较而言,布兰顿则从断言开始,依靠智识能力做出断言是人所独具的能力,因而布兰顿认为人与动物之间存在着泾渭分明的界限。

在信念的证成问题上,戴维森和布兰顿的互补性体现在:两人均以社会性的主体间交流为背景,但戴维森虑及持有信念的条件,以及证成信念的融贯论方式;布兰顿则以推论的方式为信念的证成提供了更多细节。

布兰顿相信个人总是出于某种理由而采取行动,命题内容因此总包含有意向状态,但是,如果能动者想要证明自己的言语行为(包括信念)是可信的话,他做出的断言必须能够在给出和索取理由的实践中作为推论的前提和基础,即作为推动活动的一个环节而被理解。例如,某人相信他面前的一个色块是红色的,并做出“这是红色”的断言。同时,这个人的身边还有一只鹦鹉,它同样能够说出“我相信这是红色”这个表达式。他们之间谁有权具有关于红色对象的信念呢?布兰顿认为,只有具有在推论的关系网络中定位那种对某一对象做出反应能力时,即能够知道从红色的某物中推出什么,知道什么可以作为某物为红的证据,什么与红的概念不相容时,我们才能够说某人真正做出了一个断言,该断言在给出和索取理由的游戏中能够走出一步,这一步骤能够证成其他的信念,也能为其他的信念所证成。故而,鹦鹉无权拥有一个信念,拥有一个信念至少需要知道该信念的上游和下游,鹦鹉对此一无所知。布兰顿更为强调在信念的系统中证成信念的动态步骤。

在更为深入地探究证成信念的推论过程中,我们也将会更为清楚地明白信念的公共性。以推论的方式谈论信念,实际上就需要在社会交往中接受他者的询问,信念的持有者有义务提供理由来证成他的信念。正如布兰顿所指出的,“给出和索取理由的游戏本质上是社会的实践”[10]163。

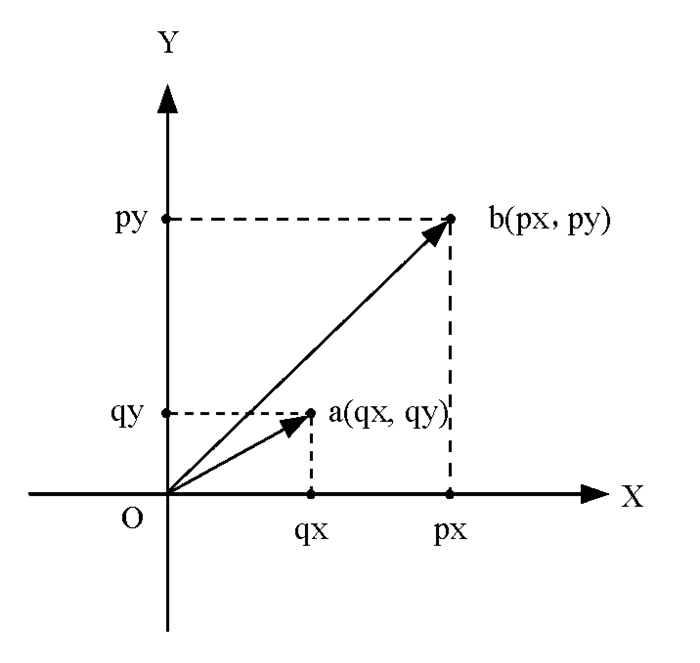

我们可以以下面的坐标图(图 1)来进一步阐释布兰顿的思想:

图中,x轴代表的是信念的维度、表征的维度,在此方向上,对于一个对象o来说,我们不妨把以o为内容的信念记作F(o)。持有F(o)的人对内容做出了从物的归因,这种归因是一种实践的态度,持有信念F(o)的人对内容o做出了“承诺”(commitment)。y轴代表的则是交流的维度、社会的维度以及推论的维度。y轴上的基本单位也是F(o),但此时的F(o)是一个判断,做出这一判断的人需要为他的判断提供理由,他需要能够在推论中走出一步。在y轴上,做出F(o)这一判断的人对这一命题享有“资格”(entitlement)。

资格和承诺是做出判断(持有信念)的人享有的两种规范身份。布兰顿指出,现实的交流中还存在道义计分者(deontic scorekeeper),他对做出判断(持有信念)的人做出计分,通过分值而认可(endorsement)或不认可做出判断的人所持有的断言。例如,给出断言的人在o点上持有的信念是“汤姆是一只狗”,在px点上持有的信念是“汤姆是雄性动物”。做出断言的人认为从“汤姆是一只狗”到“汤姆是雄性动物”是一个好的推论,在y轴上他希望自己的推论能走出这一步,他希望自己得到的分值是b(px,py)。如果计分者给做出断言的人打出分值b(px,py),那么这就说明计分者认可做出判断的人所持有的断言。然而,如果计分者发出的分值是a(qx,qy),那么这就说明计分者不认可或部分不认可做出判断的人所持有的断言。

做出断言的人同样可以成为计分者,计分者同样可以做出断言,做出断言的人和计分者两种身份的转化体现出给出和索取理由的实践中你来我往的交流,在这种交流中,分值不断变化。按照这种打分策略,似乎只有在断言被所有计分者打满分的情况下,我们才能够说做出判断的人合理地证成了他的断言,并且接受他的信念。

然而值得强调的是,布兰顿认为,道义计分者在认可某一断言时,他只是从做出该断言的人那里继承了资格和承诺,计分者本人不负有证成该断言的责任。这就意味着,计分者与做出断言的人可能有着不同的信念体系,但他们依旧可以谈论相同的对象。例如,信奉琐罗亚斯德教的人(Zoroastrian)和我们一样有着关于“太阳”的信念,但他们可能以相当不同的方式对太阳做出了从物的归因;但是,如果我们作为计分者并认可他们所作出的断言,那么,即便我们具有不同的信念体系,我们所谈论的仍是同一个太阳,因为我们一旦从他们那里继承了资格和承诺,我们就认可了他们所做出的推论,认可了作为推论的前提和结论的断言及其内容。在计分者未打出满分的情况下,计分者和断言者仍然可以在计分者可接受的分值内谈论相同的对象,持有相同的信念,从而做出成功的交流。

在上述推论的实践过程中,断言被用了两次。在第一次使用中,断言作为一种包含内容的信念而置身在一个融贯的信念体系内;在第二次的使用中,我们需要证明该断言能够作为推论的前提和基础,即既需要其他断言作为理由,又能作为其他断言的理由,在这次使用中,断言被证明是一个推论链条中合理的一环。

如果说信念是为私人所享有的,而在其相应的断言被证成和接受之后,而成为合理的、亦可以为他者持有的信念的话,我们毋宁认为信念和断言是一枚硬币的两面①,证成断言的过程实际上也是证成信念的过程。信念和断言一样都在公共的维度中获得其意义以及真值。

① 本节的论述似乎会导向如下结论:信念等同于断言。然而,我们不应就此模糊信念和断言之间的界限。我们对信念的公共性的强调使得我们承担更多的证成责任,犹如证成断言一样,这一事实拉近了信念和断言之间的距离。然而,所有的断言都具有真值,但并非所有的信念都有真假可言,例如一些伦理信念和宗教信念便无真假可言。此外,即便正常的信念与断言之间也有着区别,两者都是关于“命题”的表达式,但是信念在提供证据方面的“力度”要弱于断言,这便导致证成信念的要求也要比证成断言要宽松许多。这一事实也使得相悖于埃文斯、威廉姆斯以及威廉姆森等人观点的情形是可能的,即信念成真的条件与断言的成真条件并不同一。见WILLIAMSON T.Knowledge and its limits[M]. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000: 164-181,以及HAWTHORNE J, ROTHSCHILD D, SPECTRE L. Belief is weak[J]. Philosophical Studies, 2016, 173(5):1393-1404。信念和断言之间的关系还有待我们做出进一步的探究。

-

强调信念的公共性能够为解决关于信念的一些争论,例如“摩尔悖论”,提供新的视角。摩尔悖论的形式是“P是真的但我不相信P”或P & ~IBP,其中IB代表“我相信”[11]。举“天在下雨但我不相信天在下雨”为例,大部分人对这一表达式有着直觉上的不适感,以致几乎所有批评者都在试图证明我们不可能合法地持有这一表达式。然而细思之下,前半句(a)“天在下雨”是一个判断句,而后半句(b)“我不相信天在下雨”是一个信念句,我们需要对具有形式(P & ~IBP)的表达式的不合法性做出更多的说明。人们主要运用如下四种策略驳斥摩尔悖论:

第一种是语用的策略,用奥斯汀的话说,“说话就是做事”,这种策略认为(a)在语用上已经隐含了与之相应的信念,即“我相信天在下雨”,该信念与(b)矛盾,我们在实践中无法既相信P又相信~P,即IBP & ~IBP不可能[12]。

第二种是信念的(doxastic)策略,根据这一策略,人们不可能认为自己相信“天在下雨但我不相信天在下雨”。该策略的代表人物舒麦克提出了“关于意识的高阶思想理论”,认为某一精神状态M是意识性的,当且仅当某人能够觉识到它,因此某人有意(consciously)相信P时,他不仅相信P,还需具有二阶信念:他相信自己相信P。故而,“我相信天在下雨”的同时也需要具有“我相信-我相信天在下雨”这样的二阶信念,(a)与二阶信念相矛盾,于是摩尔悖论不可能[9]37。

第三种是认识论的策略。埃文斯和威廉姆斯都运用这一策略来说明摩尔悖论的不可能性。埃文斯认为,证成(a)的理由也构成证成(b)的理由,[13]因而摩尔悖论实际上犯了IBP & ~IBP或P & ~P的逻辑错误。威廉姆斯也持有类似的观点,认为摩尔悖论“在逻辑上是不可能的,因为任何证成我相信某物如此的事物已经使得我无权相信某物并不如此,相反的情况也一样”[14]。故而证成(b)的情境和证成(a)的情境是一样的,我们在相同的情境下不可能具有(同时证成)两个相矛盾的信念。

最后一种是解释的策略。瓦希德运用戴维森的真之语义学发展了这一策略。戴维森认为“S在语言L中是真的,当且仅当,P”,其中,P是谈论S的元语言。P既是S的翻译,也是S的成真条件;在具体的实践中,我们在探究P时,实际上是在对S做出解释。[9]45按照这种理解,当我们认为(a)为真时,我们已经对它做出了解释,获得了它的成真条件,例如在此时此地打开窗发现天正在下雨。(b)构成了与对(a)的解释相矛盾的因素,只要我们断言(a)为真,我们就无法同时持有(b)。

这四种策略有着各自的优缺点,限于篇幅,本文不拟对之做出具体讨论。笔者试图指出的是,从信念的公共性视角看,我们可以获取一种兼收上述策略优点的方法。

既然信念是公共的,如果某人持有诸如“天在下雨但我不相信天在下雨”这样的信念时,他需要在公共的领域内为之提供证成。信念相应于承诺,断言相应于资格;当某人试图获得对断言(a)的资格却对信念(b)做出承诺时,用布兰顿的话说,他所持有的推论语义学和实质语用学之间便出现了裂隙,因为推论地证成(a)和语用地使用(b)乃是同一个进程的两个方面。[10]157-184推论地证成(a)“天在下雨”这一断言的过程会使得我们同时持有“我相信天在下雨”这样的信念,而不会对“我不相信天在下雨”做出承诺。(a)和(b)的内容是矛盾的,如果我们同时持有两者,我们便会面临语义和语用的分裂,即“言行不一”。“言行一致”要求我们将说话和做事协同起来,故而信念的公共性能够容纳语用的策略。

由此看来,我们也可以接受埃文斯和威廉姆斯的认识论策略,认为对断言以及相应的信念的证成过程乃是不可分的同一个过程。同样在给出和索取理由的推论实践中,当某人持有信念(b)并对之做出解释时,他必然会以给出(b)的成真条件的方式进行。除非在特殊的情形中,我们一般试图解释为什么“天在下雨”而非解释“我相信”或“张三相信”。因而在正常情况下我们同时可以接受瓦希德的解释策略,即在解释“我相信天在下雨”时,给出“天在下雨”的成真条件,成真条件构成了a & ~b的共同理由。

此外,信念的公共性策略也可容纳信念的策略。我们要求公共性的信念的持有者至少是理性生物,这便要求他以可被理解的方式行动和说话。如果能动者认为P是真的却不相信P,他便违背了宽容原则,我们在交流中将无法理解行为如此“怪异”的能动者,以致无法和他进行成功的交流。故而,理性的信念持有者必然相信他的信念,即具有二阶信念。实际上,由于信念的非私人性,一阶信念中的“相信”所传达的主观态度,也需要在公共的维度中得到检验,这一方面要求在二阶的信念中认知一阶信念。另一方面,不同于舒麦克式的策略,笔者认为,信念的公共性模糊了一阶信念和二阶信念之间的界限,由于所有的信念本质上是公共的,每一信念都需要在一个信念整体中被认知,故而构成一阶信念认知背景的二阶信念也需要一个信念整体作为背景,对更为高阶的信念的要求实际上是对信念整体的要求。一阶信念和二阶信念只存在认识策略上的差别,即某一正在被研究的信念被视为一阶的,而其他的相关信念则被视为二阶的;当认识的焦点被转置时,信念的一阶和二阶属性可能会发生变化。如若把二阶信念的合理性依据放置在证成信念的整体论(也包括推论)的方式中,“相信”在事实上是可取消的,“相信”的措辞以及一阶和二阶的界限将消融于具体的证成过程中。信念的公共性策略在这一点上发展了舒麦克式的信念的策略。

总而言之,信念的公共性策略作为一种解决摩尔悖论的综合性策略,它容纳了语用的、信念的、解释的、认识论等策略的核心要点,该策略要求言语和行为、语用和语义、信念和断言一致,要求人们能够给出信念的成真条件,能够在公共性的空间中以推论的方式证成该信念,证成信念及其相应的断言的过程乃是同一个过程,信念和断言必须一致,这使得人们不再能够合法地持有(P & ~IBP)这种形式的表述。

-

信念的公共性使我们摆脱纯粹的第一人称视角,能动者持有信念的主观理由需要经过公共维度的检验才能够真正起到证成的效果。公共的信念的持有者虽然需要承担更多的证成责任,但也因此与共同体的其他成员更为紧密地联系在一起。强调信念(包括宗教信念)的公共性还有着重要的伦理意义[4],除了对摩尔悖论的解释之外,还有助于理解信念的灵敏度(sensibility)、安全性(safety)等问题。然而,关于信念公共性的论述本身尚存在诸多问题,我们应给予这一思想及其运用以更多的关注。

下载:

下载: