HTML

-

“不要嘲笑少年的伪装,他只是在不断的角色变换中找到真正的自己”[1]。在我们的成长过程中,总是不自觉地去探寻与自我相关问题的答案,比如“我是谁?”“我是怎样的人?”等等。对自我的认知可能是每个人究其一生都要去探索的“课题”。研究发现,青少年时期是研究自我概念稳定性与变化性的关键期[2]。寻求自我意识的发展和自我同一性的建立是青少年需要解决的首要任务[3]。他们看待自我的清晰程度会影响其主观幸福感、痛苦体验以及人际关系的发展[4-6]。自我概念清晰性(self-concept clarity)作为自我概念结构的重要组成部分,是指个体自我概念的内容被清晰和自信定义的程度,主要反映了个体自我概念的内部一致性和相对稳定性[7]。根据幸福感的自我知觉理论,当个体在理想自我和现实自我间知觉到较大差异时,容易出现自我模糊和自我不确定感,从而降低其积极情绪体验和产生消极情绪[8]。大量研究表明,自我概念清晰性对个体的心理健康和社会功能有影响,如自我概念清晰性与自尊[9-10],生命意义感[11]以及良好的情绪体验[12]呈正相关,与个体的焦虑、抑郁[13]和孤独感[14]呈显著负相关。有研究表明,自我概念清晰性会促进主观幸福感的发展[15]。但同时还有研究发现,在发展和构建自我概念的过程中,随着对自我探索频率的增加,青少年可能会滋生一些内在心理问题,比如产生抑郁和焦虑[16],且有研究发现,高自我概念清晰性的个体较易产生适应性问题,会出现自我防御性以及完美主义倾向[17-18],从而降低其幸福感水平。因此,青少年自我概念清晰性与主观幸福感的关系究竟如何?仍是一个亟待解决的问题。

主观幸福感包含两个相关但又彼此独立的成分:认知幸福和情绪幸福[19-20]。因此,本研究对认知幸福和情绪幸福分别进行探讨,其中,认知幸福是以生活满意度作为测量指标,情绪幸福则以积极情绪-消极情绪为衡量方式。基于此,本研究主要关注以下三个问题:青少年自我概念清晰性的发展呈现出怎样的类别特征?在自我概念清晰性水平上,具有不同发展模式的青少年在性别和年级上具有怎样的特点?以及不同自我概念清晰性发展水平的青少年体验到的认知幸福和情绪幸福呈现出怎样的差异?

以往,在揭示自我概念清晰性与主观幸福感的关系研究中,研究者通常从变量中心的角度进行探讨,比如,大多数研究根据被试总分或平均分的高低来判断其自我概念清晰性的水平,然后分析不同水平的自我概念清晰性与主观幸福感的关系。这种以总分或平均分的高低对被试进行分组的方式,容易忽视组内群体的异质性,从而导致结果的不准确。潜在剖面分析(latent profile analysis, LPA)是以个体中心为视角,在题项作答中,将具有相似反应模式的个体分为同一类别,通过比较不同分类模型的拟合指数来选择最优模型,提高了分类的准确性,同时,这种方法也能保证组间异质性最大化和组内异质性最小化[21-22]。因此,本研究采用潜在剖面分析的方法,从青少年自我概念清晰性的不同类型出发,分析其在性别和年级变量上的特点以及与主观幸福感的关系,为教师针对不同类型的学生进行教学辅导提供一定的参考。

-

被试来源于湖北、河北、浙江、江西、重庆和四川等地3所初高中和5所大学的2 792名学生。采取整群抽样的方法抽取初一、初二、高一、高二和大一学生,本研究认为,初中生、高中生和大学生分别处于青少年的早期、中期和晚期阶段。初中生年龄在11~15岁,平均年龄为12.86岁(SD=0.68),其中男生347人(47.3%),女生384人(52.4%),2人性别缺失。高中生年龄在13~19岁,平均年龄为15.93岁(SD=0.79),男生336人(41.7%),女生464人(57.6%),5人性别缺失。大学新生年龄在16~24岁,平均年龄为18.89岁(SD=0.98),男生522人(41.6%),女生731人(58.29%),1人性别缺失。本研究对性别缺失者进行随机插值处理。

-

(1) 自我概念清晰性

采用Campbell等人编制的自我概念清晰性量表(Self-concept clarity Scale, SCCS)简版评估处于青少年早、中、晚期学生的自我概念清晰性水平[7],共12题,其中,除了第6题和第11题,其余题目均反向计分。题项如“我很少感觉到自己不同人格方面的相互冲突”。采用7点计分(1=非常不符合,7=非常符合),分数越高,表明自我概念清晰性水平越高。该问卷的中文版本具有良好的信效度[23]。本研究中,该量表的内部一致性系数为0.80。

(2) 主观幸福感

主观幸福感由认知幸福和情绪幸福构成[20]。其中,认知幸福由生活满意度作为测量指标,采用Diener等人编制的生活满意度量表(Satisfaction with Life Scale, SWLS)来评估[24],共5题,项目如“我生活中的大多数方面接近我的理想”。采用7点计分(1=非常不符合,7=非常符合),分数越高,表明认知幸福水平越高。本研究中,该量表的内部一致性系数为0.73。情绪幸福由积极情绪与消极情绪的差值作为测量指标,采用Watson等人编制的积极消极情绪量表(Positive and Negative Affect Schedule, PANAS)来评估[25],共20题,其中,积极情绪和消极情绪各有10题。采用5点计分(1=几乎没有,5=极其多),积极情绪分数越高,且消极情绪分数越低,表明情绪幸福水平越高。本研究中,积极情绪量表和消极情绪量表的内部一致性系数分别为0.84和0.85。

-

首先通过SPSS21.0进行描述性统计,然后使用Mplus7.0进行潜在剖面分析。具体而言,先通过描述性统计分析得出自我概念清晰性、认知幸福和情绪幸福的平均值、标准差以及相关系数。其次,对青少年的自我概念清晰性进行潜在剖面分析,从二类别模型开始,逐步增加类别的数量,对比找出拟合数据最好的模型。在模型的拟合指标中,Log Likelihood、AIC、BIC和aBIC的指数越小,表示模型的拟合程度越好,Entropy指数为分类精确率,大于0.8时,表示潜在类别的分类精确率大于90%,LMR和BLRT值达到显著水平时(p<0.01),表明模型K比模型K-1的方差解释率更高,模型的拟合更优。最后,用潜在剖面分析的结果作为划分类别的依据,利用SPSS 21.0对各个类别在性别、年级中的分布及对主观幸福感的影响进行差异检验,检验水准为α=0.05。

一. 研究对象

二. 研究方法

1. 研究工具

2. 统计学分析

-

自我概念清晰性、认知幸福和情感幸福量表的描述性统计及相关分析结果如表 1所示。相关分析结果表明,青少年的自我概念清晰性与认知幸福(r=0.27, p<0.01)和情绪幸福(r=0.52, p<0.01)均呈显著正相关,且认知幸福与情绪幸福呈显著正相关(r=0.43, p<0.01)。

-

青少年自我概念清晰性的潜在剖面分析模型拟合指数如表 2所示,依次建立2~5个潜在类别。结果发现,Entropy值在4类别和5类别时小于0.8,因此,2类别和3类别比4类别和5类别更精确,方差解释率更高。而AIC、BIC和aBIC在3类别时减少的幅度达到最大,随后逐渐趋于平缓,表明3类比2类的拟合更好,因此,最终确定3类为最优潜在剖面模型。

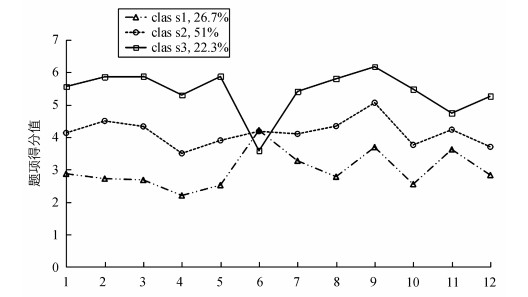

青少年自我概念清晰性的潜在类别在各题目上得分如图 1所示,第1类青少年占总人数的26.7%,相较于其他两类,该类青少年在除第6题“我很少感觉到自己不同人格方面的相互冲突”外,其他题目得分均最低,命名为低自我概念清晰性组(C1组)。第2类青少年占总人数的51%,该类青少年除第6题外,其余题目的得分高于第1类,低于第3类,命名为中等自我概念清晰性组(C2组)。第3类青少年占总人数的22.3%,该类青少年在第5题“当我回想过去的自己时,我其实不是很确定自己是个什么样的人”和第9题“如果有人要我描述我的个性,我可能每天的说法都不一样”(反向计分)显著高于第1类和第2类,命名为高自我概念清晰性组(C3组)。

-

以潜在剖面分析结果为因变量,性别(女性为参照)和年级(大一为参照)为自变量进行多项式Logistic回归分析,其中低自我概念清晰性组(C1组)作为比较参照类别,分析得出Odd Ratio(OR)系数,反映不同性别、年级在各自我概念清晰性潜在类别的比值。结果显示,与女生相比,C2组男女生无显著差异(p=0.30),C3组中男生所占比例更大(p<0.01),表明相对于低自我概念清晰性组,男生更倾向于选择高自我概念清晰性组;以大学一年级为参考水平,随着年级的增长,在C2和C3组中,OR值出现先降后增的趋势,高一年级呈现最低值,表明高一学生更可能选择C1组。结果表明,性别和年级是自我概念清晰性潜类别分组的有效预测变量(见表 3)。

-

方差分析结果表明,青少年自我概念清晰性3种潜在类别的生活满意度得分差异有统计学意义(F=76.10, p<0.01,ηp2=0.05)。事后检验发现,低自我概念清晰性组(3.65±1.09)的生活满意度得分明显低于其他两组,且中度自我概念清晰性组(3.93±0.96)和高自我概念清晰性组(4.33±1.09)之间差异显著(p<0.01)。且青少年自我概念清晰性3种潜在类别的情绪幸福(积极情绪-消极情绪)得分差异显著(F=332.58,p<0.01,ηp2=0.19)。LSD两两比较事后检验显示,低自我概念清晰性组(0.42±1.00)的情绪幸福得分明显低于其他两组,且中度自我概念清晰性组(0.65±0.83)和高自我概念清晰性组(1.31±0.87)之间差异显著(p<0.01)(见表 4)。

一. 描述性统计结果

二. 青少年自我概念清晰性的潜在剖面分析结果

三. 青少年自我概念清晰性潜在类别的人口学特点

四. 青少年自我概念清晰性潜在类别与主观幸福感的关系

-

本研究采用LPA探讨了处于早期、中期和晚期青少年的自我概念清晰性的潜在类别、分析不同类别自我概念清晰性在人口统计学变量上的特点及与主观幸福感的关系。结果发现:第一,青少年的自我概念清晰性存在三个亚类别,包括低自我概念清晰性组、中度自我概念清晰性组和高自我概念清晰性组,各组在自我概念清晰性题项上的得分(除第6题)存在明显差异。其中,中度自我概念清晰性组人数占总人数的51%,这表明,对于青少年群体而言,自我意识处于发展阶段,青少年群体依然面临自我同一性的发展任务。第二,多项式Logistic回归分析表明,性别和年级对自我概念清晰性的潜在类别具有预测作用。具体来说,相比于低自我概念清晰性组,高自我概念清晰性组中男生比女生更多;与大一学生相比,中度自我概念清晰性和高自我概念清晰性组中初一、初二、高一、高二的学生更少,且随着年级的增长,在中度和高自我概念清晰性组中,OR值出现先降后增的趋势,高一年级呈现最低值,表明高一学生更可能选择低自我概念清晰性组。第三,方差分析结果表明,不同潜在类别的青少年在认知幸福和情绪幸福上差异显著,低自我概念清晰性组的主观幸福感显著低于中度和高自我概念清晰性组,且中度自我概念清晰性组也显著低于高自我概念清晰性组。

-

目前国内外关于自我概念清晰性的研究取得了较为丰富的研究成果,但以往的研究从变量为中心的视角得出自我概念清晰性与主观幸福感关系的不一致结论[9, 18]。针对这一矛盾性的结果,本研究从个体中心视角出发探索不同自我概念清晰性的类型与主观幸福感的关系,为现有研究结果提供实证研究的证据。首先,本研究通过LPA对中国背景下青少年自我概念清晰性的类型进行了探讨。研究结果表明,中国背景下青少年自我概念清晰性可以分为三个潜在类别:低自我概念清晰性(26.7%)、中度自我概念清晰性(51%)和高自我概念清晰性(22.3%)。从各组人数概率的分布来看,青少年自我概念清晰性的分布呈现倒“U”型,中度自我概念清晰性水平的青少年最多,而在低自我清晰性和高自我清晰性类别中,青少年数量呈现均匀分布。这表明,大多数青少年的自我概念还处于发展的过程中,他们依旧面临着发展自我概念和完善自我同一性的任务。值得注意的是,低自我概念清晰性组的青少年更容易产生自我混乱感,从而导致适应性和内外化问题,体验更少的幸福感,应是学校教师和家长重点关注对象。

多项式Logistic回归分析表明,性别和年级是青少年自我概念清晰性的有效预测指标。相对于低自我概念清晰性组,男生在高自我概念清晰性组中所占比例更大,表明男生的自我概念清晰性发展水平更好。根据自我验证理论,自我信念的维持来自积极的社会反馈,温暖和谐的人际环境有利于自我和社会一致性的达成。以往研究表明,青春期的女生相对敏感,注重和他人的情感联结,她们更多地在与他人的相处中建立对自己的认同感[26],也会因此更可能经历人际关系的困扰,从而获得负向的社会反馈,产生自我不确定性。而在人际交往中,男生更愿意树立独立意识,更多地依靠竞争和能力给自己定位,对自我的认同更多的来自自身能力的水平。研究发现,青春期的男生抽象逻辑思维的发展普遍好于女生[27]。并且,男生在青春期的自尊水平不断提升,而女生则出现下降的趋势[28]。因此,青春期的男生的自我概念更容易产生一致性和相对稳定性,即出现较高水平的自我概念清晰性。

研究发现,相较于处于青少年晚期和成年早期的大一学生(18岁左右)[29],初一、初二、高一和高二年级的青少年较少分布于中度自我概念清晰性组和高自我概念清晰性组,且OR值在中度自我概念清晰性组和高自我概念清晰性组中呈现先降后增的趋势,在高一年级出现最低。这表明,高一学生更可能倾向于选择低自我概念清晰性组。研究发现,青少年期是形成抽象和分化自我概念的关键发展阶段,特别是在青少年中期(16岁)[30],自我形象的矛盾和前后不一致经常被发现[31]。随后到青少年晚期和成年早期时,认知能力和抽象逻辑思维的发展使青少年形成更成熟和相互关联的自我描述,从而提升了自我认知的内部一致性和相对稳定性。

-

对不同类别青少年的自我概念清晰性水平进行方差分析发现,青少年认知幸福和情绪幸福得分从高到低依次为高自我概念清晰性组、中度自我概念清晰性组和低自我概念清晰性组。该研究结果与以往大多数研究结论一致,即对于青少年群体而言,自我概念清晰性的发展水平越高,主观幸福感的体验更强。根据幸福感的自我理论,当理想自我和现实自我之间产生不一致时,容易产生焦虑和抑郁的症状,从而降低主观幸福感[32-33]。具有明确自我定义的个体会缩小理想和现实自我之间的差距,进而提升主观幸福感水平。研究表明,自我概念清晰性有助于满足个体的基本内心需求(能力需求、关系需求和自主需求)[34-35]。具体地,高自我概念清晰性个体通常对自我的认识更为肯定和自信,在社会交往中更愿意主动与他人建立情感联系,有助于满足对关系的需求[36];另外,研究表明,自我概念清晰性对个体的目标追求具有重要作用[15]。高自我概念清晰性的个体具有较强的希望感,即个体相信自己具有激发和维持朝向目标的动力以及能够为实现目标创造多种路径,因此其自主需求满足可能更高。此外,高自我概念清晰性的个体更倾向于对事件进行内归因,相信自己可以改变事情发生的结果,因此,其能力需求的满足可能更高[7]。进一步地,研究表明,内心需求的满足有利于促进个体主观幸福感水平的提升[37]。因此,高自我概念清晰性的个体一般具有较高的认知幸福和情绪幸福水平。

一. 青少年自我概念清晰性的剖面分析

二. 青少年自我概念清晰性的潜在类别和主观幸福感的关系

-

(1) 青少年的自我概念清晰性有低自我概念清晰性、中度自我概念清晰性和高自我概念清晰性三个亚类别,且不同潜在类别间的异质性主要表现在自我概念清晰性的程度上;(2)青少年中男生的自我概念清晰性发展水平更高;在年级上,与大学一年级学生相比,高中生的自我概念清晰性水平较低,更有可能出现自我不确定性;(3)不同潜在类别的青少年在认知幸福和情绪幸福上差异显著,低自我概念清晰性组的主观幸福感水平显著低于中度和高自我概念清晰性组,且中度自我概念清晰性组也显著低于高自我概念清晰性组。

DownLoad:

DownLoad: