HTML

-

中小学校园欺凌是一个严重的公共卫生问题[1],对卷入其中的欺凌者、受害者、欺凌-受害者均会产生短期和长期的消极影响[2-4]。准确测量和识别欺凌行为,对欺凌预防和干预方案的设计至关重要。为此,研究者开发了大量欺凌测量工具,两项系统综述研究对这些量表的心理测量属性和内容进行了分析[5-6],一项评估工具研究对这些量表进行了汇编[2]。但对这两项研究和汇编中纳入的测量工具进行分析,发现几个问题:第一,不同的测量工具采用了不同的术语描述欺凌行为。比如反应性-主动性攻击问卷[7]、多维同伴侵害和多维同伴欺凌量表[8]、学校欺凌量表[9]等。同伴攻击和同伴侵害经常被研究者用来指代欺凌行为,比如Vivolo-Kantor[6]等人对欺凌测量工具进行系统综述,析出的41篇文献中,有14篇使用了同伴侵害、12篇使用了同伴攻击去描述欺凌行为。这使得研究者和实践者在选用量表时可能产生混淆,不确定该量表是否有效测量了欺凌行为。第二,多数测量工具并未对欺凌行为进行界定,所以未全部纳入欺凌三标准[10]。比如,Cerezo欺凌问卷[11]仅测量了欺凌的攻击性标准,使得欺凌与攻击无法得以区分。第三,这两项系统综述研究和评估工具汇编主要聚焦于量表的心理测量属性和内容分析,未能对量表进行多角度分析,不利于研究者选择适合自己所需的量表。比如测量工具大多是多题项多类型工具,而实际研究中使用单题单类型测量欺凌的研究却不少见[12],从类型角度分析欺凌就是有价值的。第四,大多数测量工具开发的时间较早,经常未纳入网络欺凌和性欺凌[2],比如使用最广的奥维斯欺凌/受害问卷[13]即是如此。

基于以上分析,本文拟对目前使用的校园欺凌测量工具进行多视角分析,并对欺凌测量工具的选择和使用进行归纳与总结,以期为国内校园欺凌研究者和干预实践者在选用测量工具时提供参考依据,并为测量工具的中国化提出建议。

-

Olweus[10]将校园欺凌界定为一个或多个学生持续对不容易进行自我保护的学生实施的有意攻击。根据这一界定,校园欺凌包含重复性、力量的不平衡和伤害意图或攻击性3个标准。只有少数测量工具囊括了所有这些标准,比如奥维斯欺凌/受害问卷(修订)[13]、反应性-主动性攻击问卷[7]、雷诺兹欺凌侵害量表[14]等。

但Olweus的界定和标准受到了质疑。有研究指出,学生并不认为重复是界定欺凌的重要标准[15-16]。比如,上传一张令人难堪的图片到网络,可能长时间被多人看到而导致对受害者持续的嘲笑和羞辱。尽管这种攻击行为并没有被重复,但它导致的伤害却随着持续的嘲笑和羞辱而反复被体验[17]。Cerezo欺凌问卷[11]和同班同学提名量表[18]就未测量欺凌的重复标准。更为重要的是,大多数测量工具常把欺凌视作攻击的一种次级类型,往往没有测量力量的不平衡标准,比如欺凌行为和同伴侵害量表[19]、环太平洋地区欺凌测量量表[20]即是如此。

-

校园欺凌包含多种类型,比如身体、语言、关系、社会、网络、性欺凌和公开欺凌,直接或间接攻击,主动性攻击或反应性攻击[17, 21]。测量单一欺凌类型的量表较少,比如社会欺凌卷入量表[22]和希腊网络欺凌/受害经历问卷[23]仅测量了社会欺凌和网络欺凌;涉及多种欺凌类型的量表居多,比如伊利诺伊欺凌量表[24]。但大多数工具没能评估欺凌的所有类型,可能会低估欺凌率或受害率[25]。比如,网络欺凌行为在青少年群体中与日俱增[26],但网络欺凌经常未被测量;性欺凌是同性恋、双性恋群体经常遇到的问题,但性欺凌更少被包含在量表里[2, 6],需要通过多个量表实现对欺凌的整体评价。另外,有的研究只用一个题项评估欺凌率或受害率,不涉及任何类型,无法对欺凌行为提供深入的理解[12]。

-

校园欺凌是一个人际互动现象,卷入其中的人被划分为欺凌者、受害者、欺凌支持者、旁观者、可能的防御者和防御者[27],或者欺凌者、受害者、欺凌支持者、欺凌强化者、受害者的防御者和局外人[28]多种角色。不同角色会对校园欺凌的产生起到不同作用[2],所以研究者越来越重视欺凌行为中涉及的多个角色。参与角色问卷[28]就评估了欺凌者、欺凌支持者、强化者、防御者和旁观者;加利福利亚欺凌侵害量表[29]、伊利诺伊欺凌量表[24]同时测量欺凌者和受害者;仅关注欺凌者或者受害者的量表不多,比如反应性-主动性攻击问卷[7]仅测量欺凌者。

-

为了更为准确地评估校园欺凌,研究者可能会采用多种不同的测量方法。比如,学生自我报告、同伴评估、父母和教师评定[30-31]。不同的测量方法各有优缺点,测量是否准确不存在绝对的“金标准”[31]。但学生自我报告使用效率最高[32],比如儿童-青少年嘲弄量表[33];同伴评估则其次,比如同班同学提名量表[18]和同伴关系量表[34];可同时采用自我报告和同伴评估的量表很少,比如学校欺凌风气量表[35]。

-

为确保欺凌评估的准确性,测量工具的心理测量属性至关重要。Vessey[5]等人采用多个指标评估了工具的测量可靠性,包括重测信度、内部一致性信度、项目和总分的相关以及内容效度、结构效度、预测效度、地板-天花板效应等。结果发现测量工具通常缺乏成熟度,很多量表具有不足的测量学指标,也即信度资料通常较好,而效度资料经常不足。其他相关研究也显示,15%的测量没有报告内部一致性系数,68%没有提交内容效度的证据[2, 6]。

为了给欺凌研究者和实践者提供可选择的量表,基于以上分析,表 1列举了20世纪90年代以来囊括了欺凌三标准、通过一定的信效度评估、采用学生自我报告和同伴评估两种测量方法、适用于测量中小学欺凌行为的部分量表,并对量表涉及的欺凌类型、欺凌角色、题项数等相关内容进行了梳理。

一. 从测量的欺凌标准角度分析

二. 从测量的欺凌类型角度分析

三. 从测量的欺凌角色角度分析

四. 从测量的方法角度分析

五. 从测量的有效性角度分析

-

如何根据需要选择合适的测量工具是使用者必须考虑的问题。Russell等人[41]的研究显示,相比一般的欺凌,经历基于偏见的欺凌(如性取向)之后,学生更可能报告药物滥用、心理健康问题和糟糕的学习成绩等。如果学校咨询师希望识别和帮助因同性恋取向而遭受欺凌的学生,采用同性恋欺凌量表就比一般的欺凌量表更准确,这项研究支持了选择测量工具的重要性。

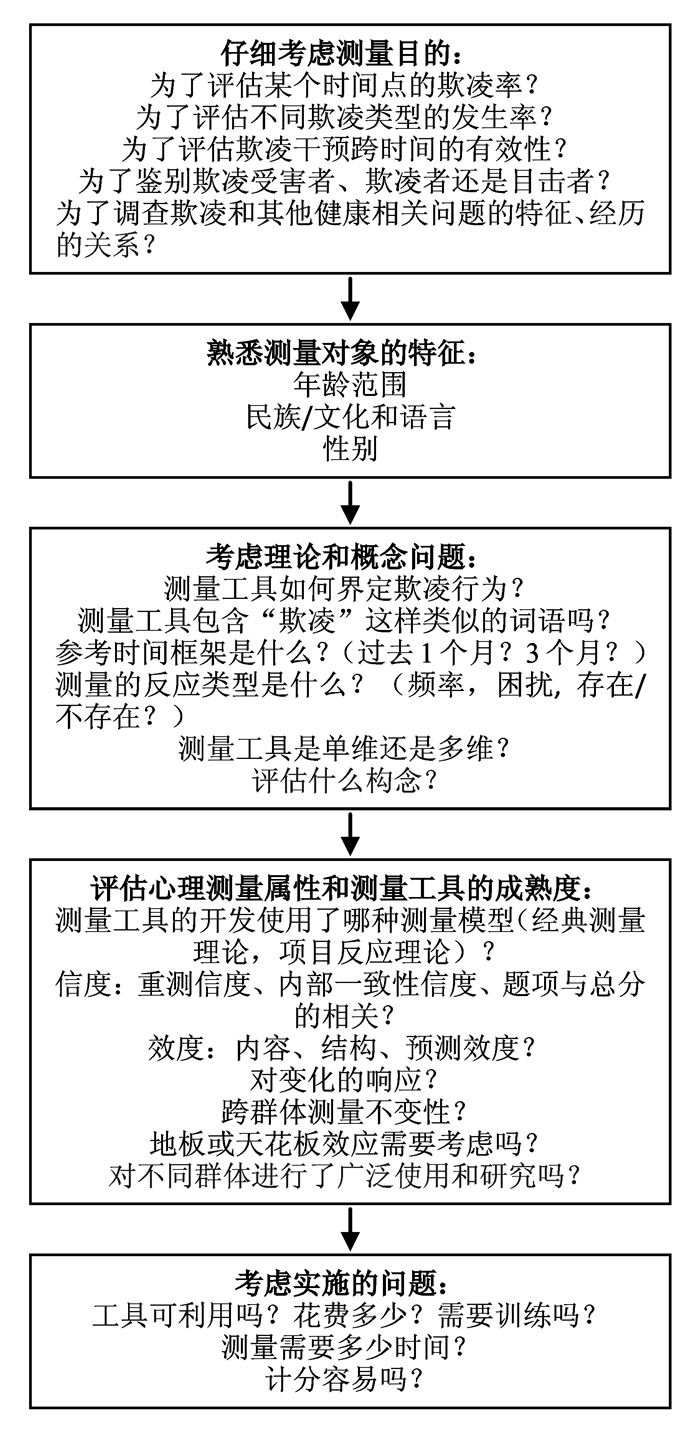

咨询师、教育者和研究者选择测量工具时,首先必须考虑测量目的。例如,教育主管部门想了解某所学校某个时间点的欺凌受害率,工具的结构效度可能就比重测信度重要;研究者如果对欺凌经历随时间变化的情况感兴趣,工具是否能评估欺凌相关行为随时间产生临床上的重要变化就是关键的测量属性[5]。其次,明确测量对象。假如测量目的是鉴别欺凌者,则选择专门针对欺凌者的工具就比针对多角色开发的测量工具更合适。第三,测量工具的理论来源和概念界定也有助于工具的选择。第四,尽可能选择经过各种信效度检验的成熟工具,但如果没有,则什么样的心理测量属性在本次使用中最重要就是需要考虑的问题。最后,对结果如何使用要有预先的计划。具体见图 1。

-

为了有效地使用测量工具:第一,在测量时应给学生提供简单易懂的欺凌定义。因为学生不会总是意识到自己被欺凌或对他人实施了欺凌。比如,38%的14岁学生并不认为排斥他人是一种欺凌行为,在回答问题时就会把关系欺凌排除在欺凌行为之外,使得测量结果不可靠[42]。第二,使用效度筛选题项[43]和事后控制技术[44]对不认真作答或作假进行识别、矫正和控制,删除无效问卷或将作假部分在数据处理时进行矫正和控制,提升自评量表的效度。研究显示,自评经常可能出现欺凌者低估、受害者高估欺凌率的情况[32],从而使欺凌行为的识别和干预受到影响。第三,当测量工具用于识别不同的欺凌角色时,选择合适的临界值作为判断标准。比如,每周几次[45]、每周1次及其以上[46]、每月2~3次[47]、得分高于平均数1个标准差以上[48]或者得分在前15%[49]的欺凌或者受害频次或得分,即可被鉴别为欺凌者或者受害者。标准有宽有严,需要根据测量目的加以选择。第四,转变教师对测量的误解,提升对欺凌测量的配合度。尽管教师经常使用测量的方法去评估学生的学习成绩,但对于欺凌的测量,教师们可能存在误解。他们认为,心理学家或者咨询师们使用培训或技能训练才是改变学生欺凌行为的最好方法[50],所以对欺凌测量存在不重视现象。然而评估欺凌行为是预防和减少欺凌行为的第一步,只有评估,才能了解欺凌行为的频率、欺凌的类型等,才能进行有针对性的干预。

一. 测量工具的选择

二. 测量工具的使用

-

尽管目前开发出的欺凌测量工具已非常丰富,但多基于西方文化背景,多基于Olweus的欺凌定义而编制[2]。由于文化、翻译等差异,使得跨文化欺凌率的比较变得困难,也会进而影响干预的有效性。比如,Olweus编制的欺凌/受害量表被广泛使用,Eslea等人[51]比较了7个国家使用这一量表测量的欺凌率和受害率,结果发现了从2%(中国)到16.9%(西班牙)的非常不同的欺凌率;从5%(爱尔兰)到25.6%(意大利)的非常不同的受害率。不清楚这种差异是不同国家校园欺凌行为的真实差异还是问卷翻译导致的。其次,不同国家的学生对bullying这个词的理解有所不同,从而影响对欺凌率的确定。比如,一项对14个国家的跨文化研究显示[52],中国孩子会使用欺凌、凌辱、欺负、欺侮、欺压、侮辱来解释bullying,而英国的孩子则使用欺凌、骚扰、嘲弄、恐吓、折磨、欺负来解释bullying。另外,同一问卷在不同国家可能存在不同的结构。比如儿童欺凌自我报告量表在澳大利亚、加拿大、日本、韩国和美国的跨文化调查中就显示出了结构不等值的情况[53]。所以有必要开发和修订出适用于中国文化的调查研究工具。

首先,中国存在特有的欺凌类型,比如班干部欺凌,《新闻1+1》报告的“火星小学事件”即为此类。测量工具的力量不平衡标准可纳入特权判断、类型可纳入班干部欺凌。其次,需要开发本土化的欺凌多角色量表。中国的“和”与“忍”文化对欺凌行为的无意识强化与确认[54],可能使受欺凌者采取更多忍让的应对方式。欺凌支持者、欺凌强化者、受害者的防御者是否会存在一些有别于国外的表现不得而知,需要有针对性的多角色量表加以测量。另外,教师和家长评估工具的开发需要跟上。中国的高考制度使教师和家长对智力教育异常重视,可能使他们对成绩优秀学生的欺凌行为产生忽视,而对成绩落后学生的欺凌行为产生刻板印象。他们会如何界定欺凌、评估欺凌的严重性不得而知,相应的测量工具尚未开发。目前,国内有学者开发出了一些测量工具,比如学校欺凌、受害和目击者量表[9]、学校欺凌严重性知觉量表[55],也有对国外量表的修订,比如对Olweus欺凌/受害量表的修订[56]等,但这项工作任重而道远。

DownLoad:

DownLoad: