-

植物功能性状是指能够响应生存环境的变化并/或对生态系统功能有一定影响的植物性状[1],它强调与生态系统过程和功能的关系[2],可以直接预测生态系统发展过程中植物群落和生态系统功能的变化[3-5],也为联系环境因子与物种特性提供了方法支撑[4],研究植物功能性状在群落间的变化有助于理解演替过程中群落结构变化及对生态系统过程的影响.

凋落物分解是陆地生态系统中养分循环的关键环节[6-7],凋落物分解快慢决定着土壤养分供应能力的大小,进而影响植被演替的进程[8].在不同演替阶段,由于植被组成和土壤条件不同,叶片功能性状随之发生改变[9-11].植物群落有效性状通过凋落叶基质质量与群落凋落叶分解速率紧密联系[10],进而影响凋落物分解及养分循环.目前相关研究多重视物种水平上凋落叶功能性状与分解的关系[12-13],也有相当多的工作关注凋落物混合分解过程[14-16],但这些工作还不足以解释群落内随着物种组成及多度变化的情况下群落水平上凋落物的分解过程.特别是在我国的西南石灰岩石漠化地区,由于生产和开发导致的群落稳定性问题十分突出,其中凋落物及分解过程对于水土保持、土壤肥力维持和生态系统内物质的生物小循环起着十分关键的作用.在特殊的石灰岩石漠化地区开展群落水平上的功能性状及与凋落物分解的相关研究,有助于我们从功能生态学的角度进一步认识石灰岩地区植被的演替过程,对于将功能性状的研究方法用于特殊生境群落水平上的凋落物分解探索也是一次新的、有益的尝试.

基于以上目的,本文以重庆市中梁山石漠化地区的灌草群落为对象,调查了人为干扰后自然恢复演替约5 a,20 a和50 a的灌草群落基本特征,对不同演替阶段群落主要木本植物叶片的功能性状及凋落叶分解进行了研究,重点探讨:① 群落水平上凋落叶功能性状随演替进程的变化趋势及其与群落演替的关联;② 凋落叶在群落水平上随演替进程的分解规律;③ 个体水平和群落水平凋落叶功能性状对其分解的预测效果.

HTML

-

研究区位于重庆市沙坪坝区中梁山北段海石公园内(29°39′-30°03′ N,106°18′-106°56′ E),是典型的喀斯特地貌,属中亚热带湿润季风气候.年均温18 ℃,海拔500~700 m,年均降水量为1 000~1 300 mm,夏季高温多雨,冬暖多雾.土壤为石灰岩上发育的山地黄壤和山地黄棕壤,由于人为干扰,在20世纪50年代末-60年代初,大量森林被砍伐殆尽,园内岩石大量裸露,土层浅薄,土被不连续,土壤富钙偏碱性,植物生长缓慢,植被覆盖率低.目前公园内主要植被是以南天竹Nandina domestica、火棘Pyracantha fortuneana、盐肤木Rhus chinensis、芒Miscanthus sinensis等为优势种的次生灌草群落[17].

-

于2014年7月在海石公园内选取人为干扰后恢复程度不同的3个典型演替阶段,即恢复5a,20 a和50 a的群落为样地(表 1),其中50 a演替阶段取10 m×20 m的样方3个,20 a和5 a取10 m×10 m的样方各3个,将大样方划分成5 m×5 m的小样方,按常规群落学野外调查方法,进行主要木本植物物种密度、盖度和频度的调查.

-

依据群落调查结果,于2014年9-11月在海石公园内采集各演替阶段主要木本物种(表 2,共16个物种)的凋落叶,置于实验室内自然风干.材料的采集及储存方法参照文献[18].

-

每物种选取10个重复(无病虫害,生理状态相似的叶片),分别测定叶干物质含量(LDMC)、比叶面积(SLA)和物理强度(LT)[18].将各物种的风干叶片用球磨仪粉碎后进行叶片元素的测定.叶片全碳(LCC)和全氮含量(LNC)利用Elementar德国CHNS-O元素分析仪测定,全磷含量(LPC)采用钼锑抗比色法测定.

-

用分解袋法进行凋落物分解实验.凋落物袋大小为10 cm×15 cm,网孔大小为1 mm×1 mm,每个分解袋内放入3 g风干样品,并订好标签.于2014年12月30日放入海石公园内条件相似的3块较平坦样地,每个样地内每物种放置3袋,于2015年6月收获带回实验室处理(共分解160 d).另外,每物种留出3份样品烘干以测量初始凋落叶的含水率.带回实验室的样品用清水快速冲洗,小心去除根和泥沙等杂物,在80 ℃下烘干至恒质量,并称量.

-

式中,IV为重要值;RD为相对密度;RF为相对频度;RC为相对盖度.

-

根据各演替阶段主要木本植物的重要值,对其相应的功能性状和分解速率予以加权赋值[9, 19],从而计算出各演替阶段主要木本植物功能性状加权值(群落植物特征的加权平均数Community Weighted-Means)为

其中,pi指该群落中第i个物种在该群落中的相对贡献率(本研究中选取重要值作为加权指标),traiti为种的特征值,S为群落中物种数.文中经过重要值加权的性状均以Ctrait表示.

-

采用Olson[20]指数模型计算凋落物分解速率

式中:Xt为分解时间t时的干质量;X0为凋落物的初始干质量;k为凋落物的年分解速率.

-

通过重要值对功能性状加权得到群落水平相对应的功能性状值,对不同演替阶段的群落功能性状和凋落叶分解速率进行one-way ANOVA分析,并运用最小显著差异法(LSD)进行多重比较;对不同演替阶段的群落功能性状、物种水平和群落水平上凋落叶功能性状与分解速率的关系进行Spearman相关性分析.采用SPSS19.0统计软件对数据进行统计分析(统计显著水平均为p=0.05),使用Origin8.6作图.

1.1. 研究区域概况

1.2. 研究方法

1.2.1. 群落调查

1.2.2. 凋落叶采集

1.2.3. 凋落叶功能性状测定

1.2.4. 凋落叶分解实验

1.3. 数据处理

1.3.1. 物种重要值计算

1.3.2. 演替阶段功能性状加权值的计算

1.3.3. 凋落物分解速率计算

1.3.4. 数据分析

-

在群落演替过程中,黄荆Vitex negundo在5 a恢复群落和20 a恢复群落中所占比例都较大,在5 a恢复群落中黄荆多为当年生或近2年生,密度大而盖度小,在群落中占较大比例,而50 a恢复群落中黄荆的萌生株数减少而实生株数增大,多为多年生植株,密度小而盖度大,重要值大幅降低.铁仔Myrsine Africana在20 a恢复群落中重要值最大,5 a恢复群落中最小,其在以草本层为优势层向以灌木层为优势层的演替发展中发挥着重要作用.山麻杆Alchornea davidii和红泡刺藤Rubus niveus属于先锋树种,在5 a恢复群落中大量存在,之后随着演替进行大幅减少.金山荚蒾Viburnum chinshanense在5 a恢复群落没有出现,但在20 a恢复群落中大量出现,到50 a恢复群落中却只出现几株,是典型的群落更替中物种更替的代表.藤刺灌木金樱子Rosa laevigata在50 a恢复群落中重要值大幅度增加(表 2).

-

随着演替的进行,20 a恢复群落的CLT和CLCC均高于50 a和5 a恢复群落,各阶段之间差异均具有统计学意义(p<0.05),但总体呈增加趋势;CLDMC和CC/N随着演替的进行而增加,CSLA,CLNC则呈现相反的趋势;50 a恢复群落的CLPC显著小于20 a和5 a,且20 a和5 a的CLPC差异不具有统计学意义;与CLPC的变化趋势相反,50 a恢复群落的CN/P最大,20 a和5 a的CN/P较低且没有显著变化(表 3).随着演替的进行,群落由高CSLA,CLNC,CLPC和低CLDMC向低CSLA,CLNC,CLPC和高CLDMC转变.

通过Spearman相关性分析(表 4),CLNC和CSLA与不同演替阶段均表现出极显著的负相关,而CLDMC和CC/N与不同演替阶段呈现出极显著的正相关,与CLPC呈显著负相关.结合表 3,CLNC,CLDMC,CC/N和CSLA随着演替的进行表现出明显的规律性变化.随着群落的不断发展,CLNC,CLDMC,CC/N和CSLA能较好地体现不同演替阶段的差异.

-

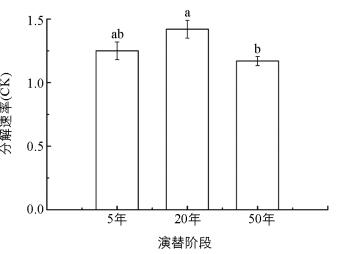

随着演替发展,各演替阶段凋落叶分解状况不同.在分解160 d后,50 a恢复群落的分解速率最小,分解最慢,20 a恢复群落的分解速率最大,分解最快,且50 a恢复群落的凋落叶分解速率较20 a恢复群落显著降低(图 1).总体来说,随演替进行,群落凋落叶分解有变慢的趋势.

-

Spearman相关性分析显示,在群落水平上与凋落叶的分解速率(CK)显著相关的性状从大到小依次为CLPC,CLDMC,CLNC=CC/N,其中CK分别与CLPC和CLDMC呈极显著的正相关和极显著的负相关. LDMC在物种水平和群落水平上均对分解有着重要的指示作用(表 5).

2.1. 物种重要值

2.2. 不同演替阶段凋落叶的功能性状

2.3. 不同演替阶段凋落叶分解

2.4. 凋落叶功能性状与分解的关系

-

群落在演替的过程中,不同物种在不同演替阶段的地位(重要值)不同,导致不同群落各功能指标的群落加权平均数也会不同. SLA可以反映植物对碳的获取和平衡的关系[21],LDMC主要反映的是植物对养分元素的保有能力[22],二者与植物的相对生长速率和资源利用有密切的关系.这说明随着演替的不断发展,群落植被由迅速获取资源型(高CSLA,CLNC和低CLDMC)转变为保持体内养分能力较强型(低CSLA,CLNC和高CLDMC),对光及土壤养分的利用效率增强,进一步促进演替. 50 a恢复群落的CLPC明显低于5 a恢复群落和20 a恢复群落,这可能是由于在土壤发育过程中,风化侵蚀使土壤中原生矿物逐渐消失,土壤中的磷酸盐从非闭蓄态的有机矿物形式转变为闭蓄态和有机结合的形式,难以利用[23],可被植物吸收的有效磷越来越有限,导致植物体各器官的含磷量逐渐降低[11].

-

在演替过程中,由于先锋树种具有养分迅速获得的生态策略,分解较快.以先锋物种为优势种的群落通过这种策略推动群落发展为更先进的演替阶段,即干扰越强的群落,其生态策略更趋向于养分快速循环型,分解较快;随着群落的恢复,其生态策略逐渐转为养分保守型,分解变慢[24].本研究中随着演替的进行,主要木本植物凋落叶分解速率呈现出先上升后下降的趋势,这可能是由于本研究在采集用于分解的凋落叶时有部分物种已经落叶,如在5 a恢复群落中占重要地位的红泡刺藤Rubus niveus;另外,5 a恢复群落临近路边,人为干扰频繁,植被生长受到较大影响,强烈干扰着群落中物种种类及数量组成等,最终导致其分解速率并没有20 a恢复群落快.但50 a恢复群落的分解速率低于5 a恢复群落和20 a恢复群落,即演替过程中主要木本植物凋落叶分解速率呈降低趋势,群落向养分保守型转变.

Kazakou等[18]发现植物的有效功能性状可以影响物种潜在的“后生命效应”对生态系统特性的影响.本研究中物种水平上LDMC与凋落叶分解的关系呈现出显著的负相关关系,SLA和C/N次之,这与之前的很多研究结果相似,LDMC是凋落叶化学组成及其分解最好的预测者[4-5, 7, 10, 25]. LDMC与土壤有机质相关,也可以反应叶片的叶肉组织与厚壁维管组织的比例[26],并与凋落叶的半纤维素含量有关[10].从群落水平来看,植物功能性状的群落加权平均数与群落的分解能力有很好的相关性,且随着演替的进行,高SLA,LNC和低LDMC的物种逐渐被低SLA,LNC和高LDMC的物种取代,分解速率也会呈现出变慢的趋势[10, 25].在群落水平上,CLPC和CLDMC与凋落叶分解的关系最紧密. CLPC的突出作用可能是由于在石灰岩地区这种特殊生境中相比N来看,P的可利用性更低,限制作用更强[27-31],从而影响凋落物分解过程中酶和微生物等的作用,这使CLPC对分解的影响比CLNC更大.另外,我国P含量的平均水平明显低于全球,而本研究中20 a恢复群落和50 a恢复群落的P含量和N/P均低于全国灌木平均水平(P=1.11 mg/g,N/P=14.7)[32],这说明本研究点主要木本植物P含量受到很大的制约,尤其是在演替后期阶段.

在本研究中,LDMC对凋落物分解有较好的预测作用,在物种水平和群落水平上达到了一致性.如果该结论被大量群落研究证实,我们可以通过简单、易测量的有限物种的相关性状来预测物种非常丰富的群落的生态系统特性,获得生态系统功能方面的重要信息,并描述和预测从物种水平上升到生态系统的物质循环.群落水平上LDMC的变化可以较好地反映群落演替过程中植被生态对策的转变,且与群落水平上凋落叶分解关系密切,能较好地反映群落演替过程中其生境状况、植被生长情况及生态系统过程的变化.

DownLoad:

DownLoad: