-

开放科学(资源服务)标识码(OSID):

-

作为当今最热门的碳负排放技术选项之一[1],生物质炭(生物质经高温热裂解过程产生的一种固态富碳多孔物质)不仅具备改土培肥[2-3]和减轻污染[4-5]等农艺和生态功能[6-7],更是降低碳排放[8]、缓解气候变化的有效路径[9]. 据估计,到2050年,全球每年可有0.3~2 Gt CO2通过生物质炭实现封存[10],相当于每年化石燃料排放CO2的0.8%~7.2%. 丁仲礼院士在《中国“碳中和”框架路线图研究》报告中也指出:中国可通过生物质炭实现每年0.2 Gt的CO2封存量. 目前,我国生物质炭的年潜在产能约100万t[11],以60%的含碳量换算为CO2当量约2.4×106 t,即可中和0.002 Gt的CO2,与0.2 Gt CO2封存量相差100倍;此外,当前生物质炭的生产和使用成本约1 400~3 700元/t,远高于其施用所带来的平均效益600元/t[12],这在经济上决定了利用现有技术极难将生物质炭潜在产能转化为实际生物质炭的产能[13],因而与碳中和目标的实现尚有很大距离.

限氧高温热裂解技术是当前制备生物质炭的主流方法[14],其高生产和使用成本主要体现在因需要专用场地和设备限氧所带来的原料与产品的运输费上[15]. 毫无疑问,限氧对于成炭不可或缺,但是否需要专门设备来限氧,则直接关系到生物质炭的生产成本. 若能将生物质就地炭化和封存,则可大幅降低生物质炭的成本[16]. 受南美洲亚马逊流域黑土形成史[17-18]和森林火灾衍生木炭的启发[19],Xiao等[20]通过系列研究提出了“水-火联动”就地炭化生物质的方法,将其成炭过程总结为生物质在曝氧环境下的“自限氧-水淬灭”高温热裂解过程(以表面灰化实现内芯炭化,通过淋水淬灭成炭),并通过分析比较限氧和曝氧炭化过程,将限氧热裂解过程中影响炭品性质的升温速率和保留时间在曝氧炭化下总结为暴露时间:火墨跌落地面至淋水淬灭前的时段. 其中,火墨指燃烧体跌落至地面形成的通体透红的高温物质;参照炭化温度引入了成炭温度:淋水淬灭前火墨表面的温度. 研究进一步量化了暴露时间对刺槐制备的生物质炭性质的影响,指出采用“水-火联动”法生成的刺槐炭的碳含量、比表面积、—COOH和phenolic—OH含量均随着暴露时间的延长而降低,以0 min暴露时间炭品的碳含量较高. 不足之处在于,因其成炭过程为以表面灰化实现内芯炭化,有较多的成分随着曝氧燃烧生成了灰分和CO2. 其生成的棉秆、芦苇和竹柳炭的碳含量介于40%~60%[21],与国际优质炭(C含量≥60%)的标准尚有距离[12]. 可见,利用该技术生产生物质炭的碳截留潜力还有待提升. 近年来,一些矿物改性、限氧制炭的研究表明[22-23],掺Ca共热解可提升生物质炭的碳截留量,Ca不仅通过催化作用加速了热化学反应,还以物理阻隔(CaCO3包裹形成保护壳)和化学键桥(阻止C=O键进一步断裂生成气体COx)的方式截留了碳.

鉴于此,本研究选取大宗生物质废弃物玉米芯为原材料,设想通过在曝氧炭化过程中设置饱和石灰水涂层形成包覆壳创造限氧条件,以提高成炭过程中的碳截留量,并初步探究Ca2+在炭化过程中的作用,为优化“水-火联动”方法成炭提供理论依据和技术支撑,以生物质炭负排放方案的技术革新助力碳中和目标的实现.

HTML

-

玉米芯:筛选笔直且长度和粒径均匀(长14 cm、切面直径2 cm)的玉米芯若干(单枝玉米芯平均质量为20.76±2.58 g),经去离子水洗去其表面附着物,烘干后称质量. 随后移至样品盒(长×宽×高=198 mm×95 mm×42 mm)备用.

饱和石灰水:以氢氧化钙分析纯(天津市登峰化学试剂厂)制备饱和石灰水. 分别称取多份1.74 g的分析纯,各自移至1 L的容量瓶中混匀,制得饱和石灰水涂层溶液. 将涂层溶液移至玻璃瓶中,于4 ℃的冰箱中冷藏备用.

-

试验设置:试验分为两种处理方式,即无饱和石灰水涂层和有饱和石灰水涂层(使用饱和石灰水作为涂层进行包覆),每种处理设有4组重复. 参考现有的研究[20, 24],每种处理设0,0.5,1,2.5,5 min为暴露时间,旨在减少暴露时间过长对生物炭成炭率及性质的不利影响. 试验优先筛选获得高碳转化率的适宜暴露时间,进而比较饱和石灰水涂层对玉米芯炭性质的影响.

样品前处理:将烘干后的玉米芯分别浸没在去离子水(保证前处理过程一致性)和饱和石灰水中48 h(一方面充分形成涂层包覆壳,另一方面保证Ca(OH)2充分浸入玉米芯内部),以形成饱和石灰水涂层,取出,备用.

制炭操作过程:玉米芯炭的制备在肇庆市鼎湖区沙浦镇广东省环境健康与资源利用重点实验室生态试验站(23°08′69″N,112°41′52″E)进行. 具体操作如下:将玉米芯置于自制的多空格铁质圆轨上(玉米芯卡在相邻的转轴间均匀自转,转速2 s/周,保证其在引燃和自燃过程中受热均匀),使用液化天然气(外焰温度:780~860 ℃)引燃玉米芯,玉米芯自燃后终止引火,待燃烧的玉米芯形成火墨时计时,分别在0,0.5,1,2.5,5 min暴露时间下将无饱和石灰水涂层的玉米芯火墨浸没在盛有去离子水(300 mL)的样品盒中,将有饱和石灰水涂层的玉米芯火墨浸没在盛有饱和石灰水(300 mL)的样品盒中,淬灭成炭后将其取出. 试验过程中同步采用自主研发的制炭尾气处理系统进行烟气处理,确保烟气排放达标[21].

样品收集:将盛有炭化物的样品盒置于烘箱中烘干(105 ℃). 取出浸水淬灭烘干的玉米芯炭,称质量(mB),标记为Biochar. 移出浸饱和石灰水淬灭烘干的玉米芯炭,称质量(mCa-B),标记为Ca-Biochar,使用玛瑙研钵研磨炭样品,过100目筛,烘干(105 ℃),备用.

-

相关性质测定:① pH值:玉米芯炭与去CO2超纯水按1∶10混合(w/v,160 r/min震荡24 h)后,离心(w/v,3 500 r/min离心20 min)、过滤,待体系平衡后用pH计(Five Easy Plus,METTLER TOLEDO)进行测定;②灰分含量:将玉米芯炭置于马弗炉(中环SX-G18123),800 ℃灰化处理4 h(温度上升至800 ℃开始计时)后其残余灰渣量占总物料质量的百分比;③ C,H元素含量:采用元素分析仪(Vario MACRO cube,德国Elementar)进行测定分析;④官能团含量:采用国际腐殖酸协会(International Humic Substances Society,IHSS)提供的酸碱滴定法测定玉米芯炭的—COOH和phenolic—OH含量;⑤比表面积:采用氮气吸附BET法在全自动比表面积和孔径分布分析仪(Autosorb-iQ,美国Quantachrome)上进行分析测定;⑥采用FTIR(Thermo Fisher Nicolet iS5)对无和有饱和石灰水涂层下玉米芯炭官能团变化进行定性分析(扫描范围为500~4 000 cm-1,分辨率为2.0 cm-1),同步采用高分辨率的扫描电镜(SEM,日本日立,S-4800)观察无和有饱和石灰水涂层下玉米芯炭表面形貌的变化[20].

关键指标:以生物质炭作为负排放方案,不仅要考虑单位质量生物质的成炭率,还需考虑其生成的炭品的碳含量百分比;鉴于此,本研究提出碳转化率(Carbon conversion rate,CCR),以表征单位质量生物质在炭化过程中的碳截留能力,计算公式如下:

无饱和石灰水涂层包覆浸水淬灭玉米芯炭:

式中:m为供试玉米芯的质量(g);mB为无饱和石灰水涂层包覆、水淬灭下生成的玉米芯炭的质量(g);C0为玉米芯的含碳量(%);C1为Biochar的含碳量(%).

饱和石灰水涂层下浸饱和石灰水淬灭玉米芯炭:

式中:mCa-B为饱和石灰水涂层包覆、饱和石灰水淬灭下生成的玉米芯炭的质量(g);C2为Ca-Biochar的含碳量(%).

采用Excel 2021进行数据管理,IBM SPSS statistics 21进行统计分析和差异性检验,以单因素方差分析(one-way ANOVA)检验玉米芯炭的C,H元素含量、碳转化率、灰分含量、pH值、比表面积、—COOH和phenolic—OH含氧官能团含量等差异是否有统计学意义(p<0.05),同时,对以上指标值进行Pearson相关分析,确定各指标间的联系,使用Origin 2021进行图件绘制.

1.1. 供试材料

1.2. 试验方法

1.3. 玉米芯炭的表征分析

-

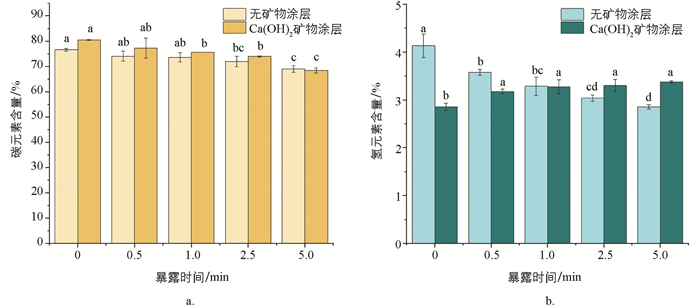

玉米芯炭元素组成及含量的分析结果表明(图 1),随暴露时间延长,无饱和石灰水涂层玉米芯炭的C,H含量均呈现出逐渐降低的规律. 原因在于火墨长时间暴露在空气中,其所含的C,H会逐渐被高温氧化,以水汽或碳氧化物的形式消耗. 饱和石灰水涂层下,C含量随暴露时间的延长而降低. 相反地,H含量随暴露时间的延长而增加. 究其原因可能为:涂层提供了限氧环境,使得玉米芯内的H和O在长时间的包覆壳限氧过程(类似于限氧成炭过程中保留时间的延长)中生成了较多的—COOH和phenoilc—OH含氧官能团.

-

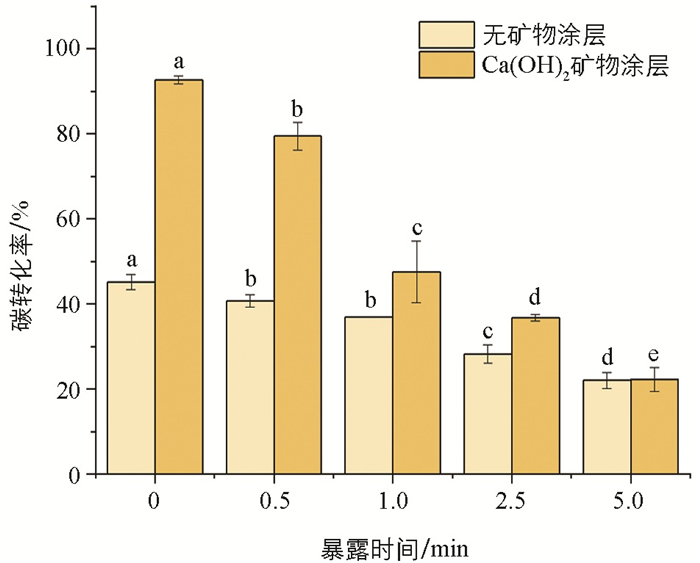

“水-火联动”曝氧炭化下碳转化率的分析结果表明(图 2),随暴露时间延长,无和有饱和石灰水涂层下玉米芯的碳转化率均呈现出逐渐降低的规律,以0,0.5 min玉米芯的碳转化率较高;进一步研究发现,饱和石灰水涂层可显著提高玉米芯的碳转化率,较无饱和石灰水涂层处理,0,0.5 min玉米芯的碳转化率分别提高了51.22%,48.79%. 究其原因可能为:火墨在成炭前处暴露自燃状态,其所含的碳会与空气中的氧结合,以COx(CO和CO2)的形式损失掉,暴露时间越长,碳损失量也就越大. 饱和石灰水涂层下,涂层包覆壳充当了“限氧炉”的“炉壁”,可通过物理阻隔的方式减小火墨中的碳与空气中氧的接触面. 另外,溶液中的Ca2+也可能通过多种形式阻止C=O键断裂生成气体COx,进行碳截留.

-

暴露时间和饱和石灰水涂层影响下玉米芯炭的灰分含量和pH值数据结果显示(表 1),无和有饱和石灰水涂层下生成的玉米芯炭的灰分含量均呈现出随暴露时间延长而逐渐升高的规律,但水淬灭玉米芯炭的灰分含量间无明显差异,饱和石灰水涂层下淬灭生成的玉米芯炭在0~0.5 min与1~5 min暴露时间下灰分含量变化差异明显. 对于pH值,Biochar的pH值随暴露时间延长而增加,以0~0.5 min与1~5 min暴露时段差异明显;相反地,Ca-Biochar的pH值随暴露时间延长而降低,大致以0~0.5 min与1~5 min暴露时段差异较明显. 一般而言,碳转化率与灰分含量呈相反趋势. 同时,灰分含量越高,炭品的pH值也就越大. 而Ca-Biochar的pH值呈现出与灰分含量相反的规律,其原因可能与饱和石灰水涂层和Ca2+影响下主要官能团(—COOH和phenolic—OH)量的变化有关.

-

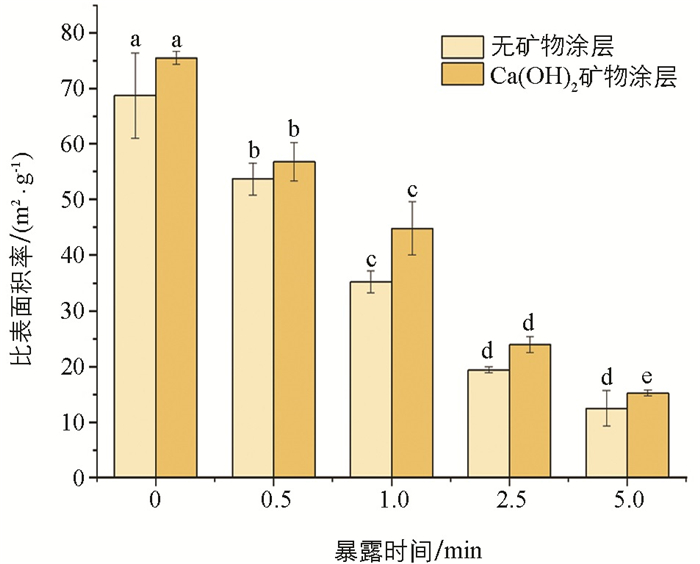

曝氧炭化所得炭品的比表面积与暴露时间和饱和石灰水涂层的数据结果表明(图 3),随暴露时间延长,无和有饱和石灰水涂层下玉米芯炭的比表面积均呈现出逐渐降低的规律,且不同暴露时间下生成的玉米芯炭的比表面积差异有统计学意义. 同时,饱和石灰水涂层可进一步提高玉米芯炭的比表面积,较无涂层处理,0,0.5,1,2.5,5 min玉米芯的比表面积分别提高了9%,6%,21%,19%,18%. 通常随着火墨暴露在空气中持续燃烧,会伴随有碳骨架发生崩塌,炭孔隙被填充,比表面积逐渐降低[24]. 当火墨完全燃烧殆尽形成灰分时,其比表面积就会降到最低[19]. 饱和石灰水涂层下炭的比表面积增大,可能是由于浸入在玉米芯中的Ca2+在炭化过程中优化了碳骨架结构,引起比表面积的增加.

-

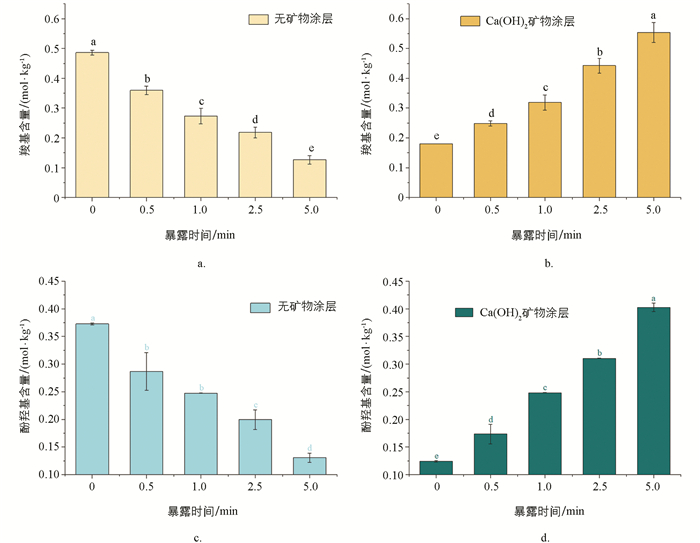

水淬灭成炭所得玉米芯炭的—COOH和phenolic—OH含量分析结果表明(图 4a,4c),随暴露时间延长,玉米芯炭的—COOH和phenolic—OH含量均呈现出逐渐降低的规律,且不同处理间差异有统计学意义. 整体上以0 min暴露时间玉米芯炭的—COOH和phenolic—OH含量最高,其—COOH含量为0.49 mol/kg,phenolic—OH含量为0.37 mol/kg. 玉米芯经曝氧高温热裂解过程形成的—COOH和phenolic—OH官能团会因火墨长时间暴露在空气中而逐渐被氧化消耗,是随暴露时间延长炭品所含官能团逐渐降低的原因之一. 相反地(图 4b,4d),饱和石灰水涂层后玉米芯炭的—COOH和phenolic—OH含量均呈现逐渐增加的规律,且各处理间差异有统计学意义. 这一变化趋势可能源于:①饱和石灰水涂层提供了限氧环境,使得玉米芯中的H和O在较长的包覆壳限氧过程(可类比于限氧成炭过程中保留时间的延长)中形成了较多的含氧官能团. ② 0 min和0.5 min暴露时间下生成的—COOH和phenolic—OH官能团在较高的成炭温度下(通常暴露时间越短,成炭温度越高)容易与Ca2+结合,在截留碳的同时消耗了大量含氧官能团.

-

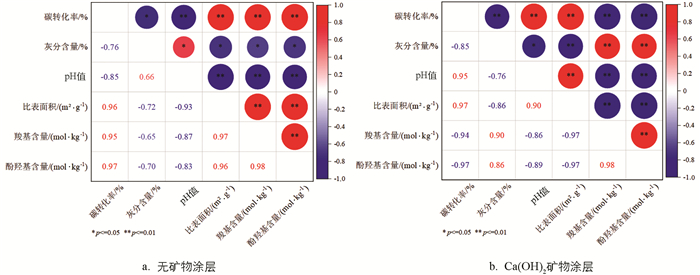

无和有饱和石灰水涂层成炭下炭品系列指标值的相关性分析结果表明(图 5),Biochar的碳转化率与比表面积和官能团含量呈正相关,与灰分含量及pH值呈负相关. 表明较高的碳截留量有助于生成高比表面积和高官能团含量的炭品,同时降低炭品的灰分含量和pH值. 关于Ca-Biochar,①其碳转化率与比表面积呈正相关,即较高的碳截留量有助于生成高比表面积的炭;②相反地,其碳转化率与官能团含量负相关,这可能与碳截留过程中需要消耗一部分官能团有关;③其官能团含量与pH值负相关,—COOH和phenolic—OH官能团呈酸性,因而其含量越高,炭品的pH值也就越低.

-

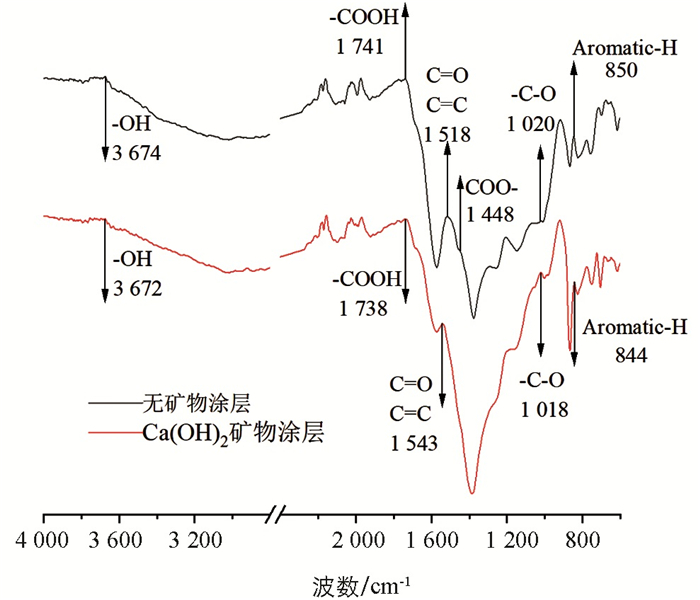

选取0 min暴露时间的水淬灭和饱和石灰水淬灭的玉米芯炭样品,通过傅立叶变换红外吸收光谱定性了其官能团变化特征. 红外光谱结果表明(图 6),①饱和石灰水涂层下—COOH,phenolic—OH的吸收峰均出现了红移,意味着震动所需的能量变低,基团不稳定,表明上述官能团与溶液体系中的Ca2+发生了反应[22];② COO-峰消失,可能是由于Ca2+与其发生了络合反应[23];③ Aromatic-H吸收峰发生了红移,可能源于Ca2+与π电子相互作用[25]. 以上现象均表明饱和石灰水涂层下Ca2+通过多种途径与炭化物中的含氧官能团发生了反应,有效阻止了C=O键断裂生成气体COx气体,进而提高了碳截留量.

-

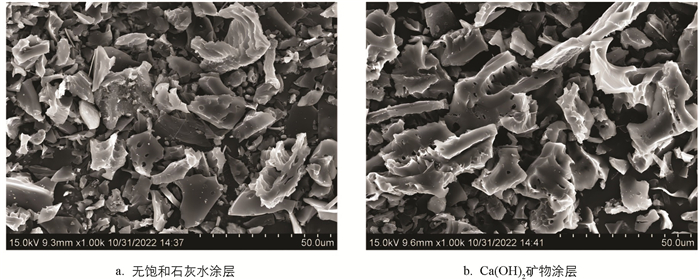

0 min暴露时间下无(图 7a)和有饱和石灰水涂层(图 7b)的玉米芯炭样品扫描电镜图谱表明,无饱和石灰水涂层下的SEM图谱碳骨架结构无序,碳间隙间存在较多的絮状物质(可能为灰分),而Ca(OH)2矿物涂层处理的玉米芯炭的碳骨架结构较为规整,存在明显孔隙且碳间隙间的絮状物质较少,该结构有利于高比表面积炭品的成型.

2.1. 暴露时间和饱和石灰水涂层对玉米芯炭性质的影响

2.1.1. 元素含量

2.1.2. 碳转化率

2.1.3. 灰分含量和pH值

2.1.4. 比表面积

2.1.5. 官能团含量

2.2. 暴露时间和饱和石灰水涂层影响下碳固存成因分析

2.2.1. Biochar和Ca-Biochar指标值相关性分析

2.2.2. 无和有饱和石灰水涂层FTIR图谱的变化情况

2.2.3. 无和有饱和石灰水涂层SEM图谱变化特征

-

“水-火联动”曝氧炭化过程中玉米芯会经历如下燃烧过程[26-27]:①引燃初期,玉米芯表面燃烧并炭化,其内芯仍为未燃烧的木质部分;②燃烧中期,玉米芯表面逐渐灰化,内芯则处于高温限氧的自燃状态,通体燃烧后结构变化、质量变轻,容易发生上翘、折断,直至跌落形成火墨;③燃烧末期,火墨逐渐灰化,最终成为灰烬. 若在火墨跌落后及时淋水,其温度骤降,淋水充足便会熄灭,生成生物质炭. 为进一步理解其炭化过程,可设想每枝玉米芯为一个微型限氧炉,表面与空气接触部分类似炉壁,内芯相当于炉内薪柴,其炭化过程为物料的表面起限氧作用、内芯进行高温热裂解的过程,即以表面灰化实现内芯炭化的过程,或称生物质在曝氧环境下的“自限氧-水淬灭”高温热裂解过程. 燃烧中期形成火墨后,暴露在空气中的时间越长,所含的碳等元素被空气中O2消耗的量也就越大,碳截留量随之降低(图 2)、同时会伴随碳骨架结构崩塌、H元素含量降低(图 1)、灰分增加[28](表 1),进而引起比表面积(图 3)和官能团含量降低(图 4a,4c)、pH值(表 1)增加等.

Ca(OH)2矿物涂层处理后,一方面,涂层形成的包覆壳可进一步充当“限氧炉”的“新炉壁”. 通过物理阻隔作用降低炭化物与O2的接触面,提高碳截留量(图 2),这与Nan等[22]的研究结果类似,其发现掺钙共热解下CaCO3包裹形成保护壳以物理阻隔的方式提高了生物质炭的碳含量;另一方面,Ca2+可通过阳离子架桥[22]、络合反应[25]、Ca2+与π电子相互作用[28-29]等形式与炭化物的含氧官能团发生作用,阻止碳氧键断裂生成碳氧化物并优化碳骨架结构(图 7),进而提高碳截留量(图 2)和提升炭品的比表面积(图 3),图 6中无和有饱和石灰水涂层条件下相关含氧活性基团的变化较好地证明了上述反应过程的发生[30]. 饱和石灰水涂层后,—COOH和phenolic—OH官能团含量随暴露时间的延长而增加,进而引起pH值的降低. 一方面,饱和石灰水涂层提供的限氧环境使得玉米芯中的H和O在较长的包覆壳限氧过程中(可类比于限氧成炭过程中保留时间的延长)形成了较多的含氧官能团[31-32];另一方面,0 min和0.5 min暴露时间下生成的—COOH和phenolic—OH含氧官能团在较高的成炭温度下容易与Ca2+结合,在截留碳的同时部分H被反应置换[24, 33].

我国农林生物质废弃物数量庞大,仅农作物秸秆年产量就高达10.2亿t[34],这为生物质炭的制备提供了大量的原材料. 但目前我国生物质炭的年潜在产量与0.2 Gt CO2封存量目标相差近100倍,说明利用现有技术生产生物质炭仍具有一定的局限性,这突出表现在利用现有技术生产生物质炭的产量有限、价格昂贵,因而目前多见于科研和小规模示范用途,少有商业化应用的典型案例. 这迫切需要在现有技术的基础上补充、创新和发展新的炭化技术,以实现生物质炭负排放技术助力碳中和目标. 饱和石灰水涂层技术匹配“水-火联动”方法的制炭流程操作简单、成本低廉,可有效地提升玉米芯的碳转化率、优化碳骨架结构并提高玉米芯炭的比表面积等,本研究可为生物质炭负排放方案提供理论基础与技术支撑.

-

1) “水-火联动”曝氧炭化下其成炭过程为玉米芯在曝氧环境下的“自限氧-水淬灭”高温热裂解过程,其生成的炭品性质主要取决于暴露时间,随暴露时间延长,玉米芯的碳转化率(由45.17%逐渐降至22%)、炭品的—COOH,phenolic—OH官能团含量、比表面积均呈现出逐渐降低的规律.

2) 饱和石灰水涂层可显著提高玉米芯炭的碳转化率,以0~0.5 min暴露时间下的碳转化率较高(92.60%~79.42%). 一方面,涂层形成的包覆壳作用降低了炭化物与O2的接触,提高了碳截留量;另一方面,涂层中的Ca2+通过多种方式阻止碳氧键断裂生成碳氧化物,进一步提高了碳截留量并优化了碳骨架结构.

DownLoad:

DownLoad: